Bike City Amsterdam tells the recent history of Amsterdam as seen from the bicycle. Around 1960, cyclists found themselves under pressure, but in following decades they managed to regain the streets. That was not without a lot of effort. In ten chapters the book shows how the bicycle regained its role as the most important means of transport in the city, and which factors contributed to this. Here is a brief summary per chapter.

Chapter 1

The bike under pressure

Things were going badly for bicyclists in Amsterdam around 1960. Tens of thousands of bikes were still filling the city’s streets every day, but bike use was rapidly declining. Biking became more unpleasant and dangerous due to the explosive use of the car in a city that was not built for it. Experts and politicians everywhere in Europe embraced new traffic models based on complete motorization of private and public transport. Pedestrians got a refuge here and there, but a biking public was left out of these visions of the future. In many cities this approach was pursued with rigor, so that for decades the bicycle there became a rarity. Things were slightly different in Amsterdam.Chapter 2

Hidden Benefits

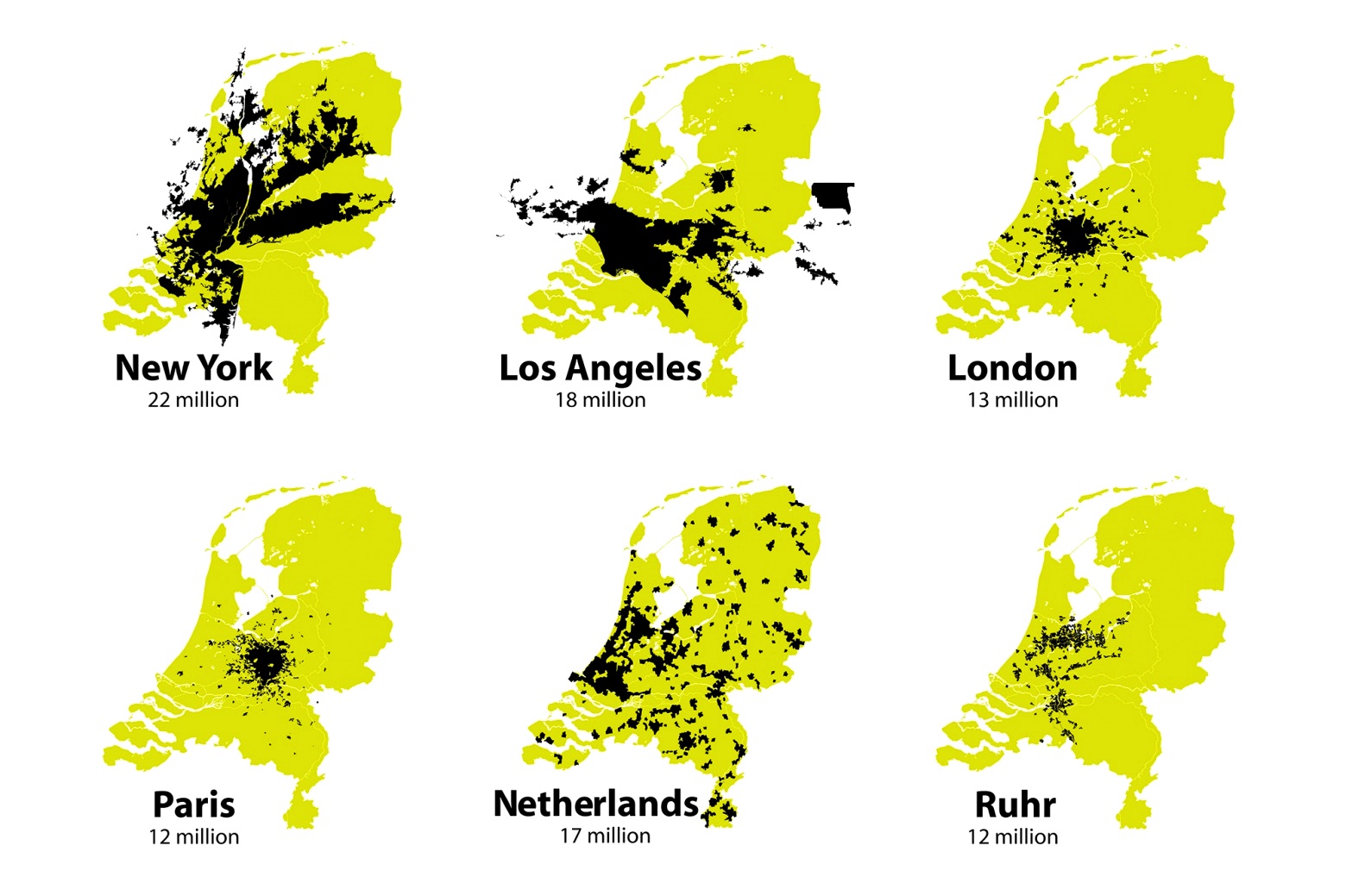

The fact that the bicycle did not die out in Amsterdam but indeed revived is due to several factors. One was the structure of the city. The Netherlands has traditionally been a country of medium-sized cities, where everyday destinations remain within a radius of a few kilometers, and therefore within cycling distance. Moreover, Amsterdam escaped major urban remodeling in the nineteenth century; no broad boulevards were built that later could absorb large numbers of cars. In the small-scale city the automobile -- driving and standing still -- was at once a problem. This meant, in the long term at least, a favorable starting point for every competitor of the car, including the bicycle.Chapter 3

Vehicle of the revolution

The bicycle also got a boost thanks to the social, cultural and political earthquake of the sixties and seventies. A new generation questioned the values of post-war prosperity, expressing its concerns about pollution, depletion of raw materials, poor quality-of-life and insecurity, and seeking better alternatives. Provo and Kabouter activists led the way, along with a large variety of other action groups. The bicycle played a role in this broad movement as a matter of course: sometimes as a main character, often as a means to other goals, always as a symbol, and simply as the most suitable means of transport for every campaigner. From a loser in the prosperity race, the bicycle became a moral winner.Chapter 4

A permanent home

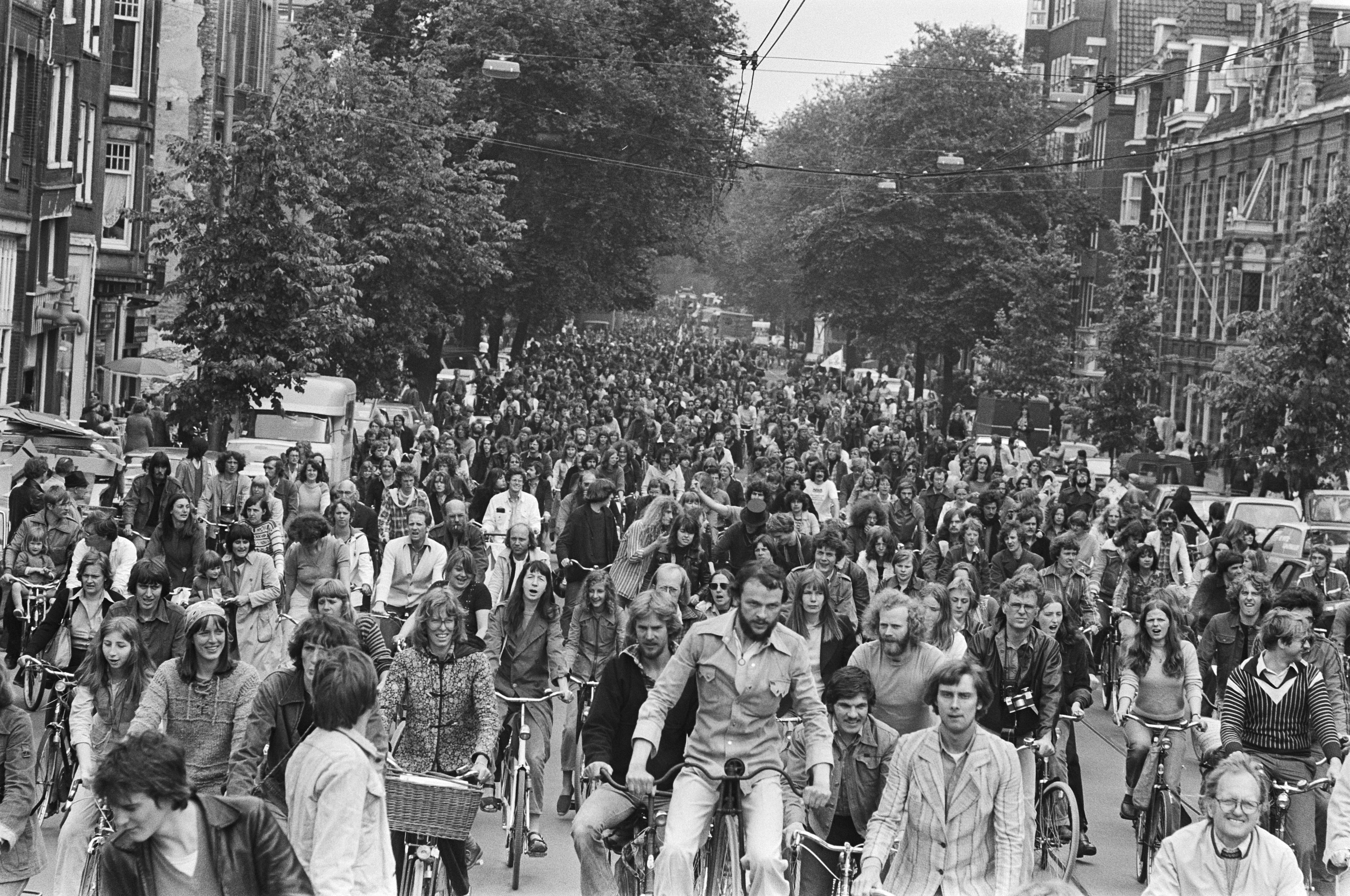

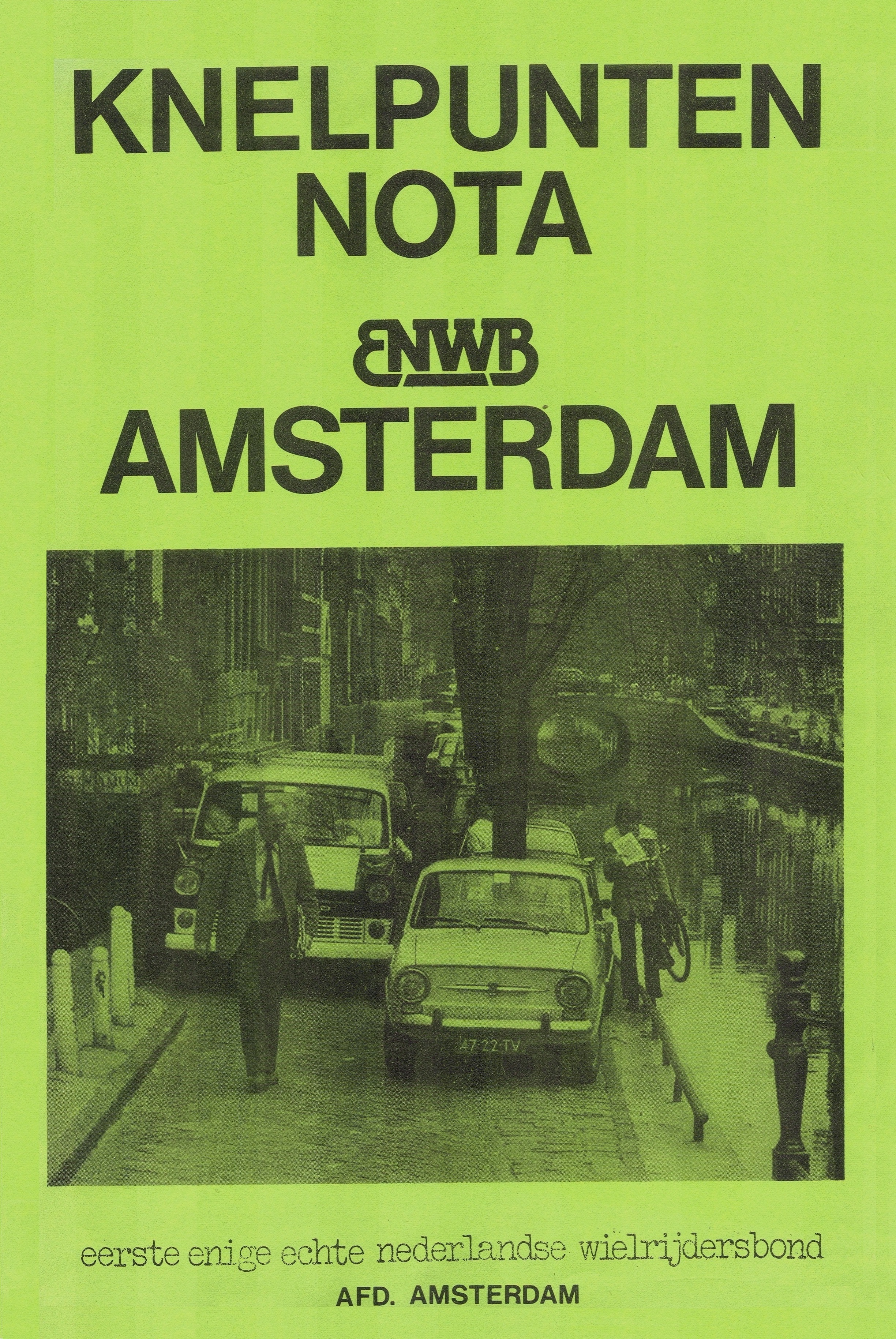

Amidst a broad spectrum of activism, some groups focused specifically on cyclists' interests. As a counterbalance to the dominant car, they sought to build up power around the bicycle. This required more than just anger, but notably knowledge, organization and patience. Knowledge was acquired through meticulous inventories of the city from the cyclist's point of view: what is important for the cyclist, where the bottlenecks are found and how they can be remedied. Large bicycle demonstrations made the power of citizen numbers manifest. With the founding of the national Fietsersbond (Cyclists’ Union) in 1975, and its Amsterdam chapter a year later, the bicycle had a fixed address. From here on, the patient work of building bike city was begun.Chapter 5

Amsterdam takes a turn

The new vision of the city, with a key role for the bicycle, was adopted by the municipal authorities in the late 1970s. Instead of a city that was expanding further and further, city government now sought the "compact city". In addition to urban renewal and redevelopment of old port and industrial areas, this also included the promotion of bicycles and public transport and the taming and containing of the car as a consumer of space. City Councilor and Alderman Michael van der Vlis laid the foundation for urban cycling policy and worked with the Fietsersbond as a platform for citizen interests and as a source of knowledge. Thereafter, policy implementation often went terribly slowly, but at least it moved in the right direction.

Amsterdammertjes: posts to prevent illegal parking

Chapter 6

Redesigning the street

The course was set; now the goals of the cycling city had to be achieved. It was and is a long-term affair. While the number of cars continued to grow nationwide, their presence in the city was curtailed and regulated. With the curbing of car parking, space could once again be created for fearless cycling. A network of cycle routes spread across the city, residential streets became traffic-calmed, hundreds of bottlenecks were tackled. Every new street plan requires working out with limited square meters amid clashing interests. As the bike become ever more successful, bike parking becomes more difficult. In this way, the cycling city progresses and remains unfinished.Chapter 7

‘It was hot, it was fun’

In the 1990s, results of the patient construction of the cycling city began to become noticeable. Foreign visitors were even more aware of this than most Amsterdammers themselves. Bike demonstrations gradually became into bicycle parties. The bicycle contributed to the renewal of city life and public space, and thus got an even stronger boost. With this, the bicycle also faced other metropolitan phenomena such as gentrification and the threat of spatial and social segregation: a sign of the increasing integration of the bicycle in the city.

Urban family-mobilty